The Rare Earth Panic: How the Narrative Outpaces Reality

In recent years, the subject of rare earth elements, or REEs, has taken on a mystique that far exceeds their actual economic significance. Headlines warn of shortages, embargoes, and even geopolitical warfare, portraying these minerals as the linchpins of technological supremacy. China, the dominant producer of REEs, has occasionally flexed this dominance, leading to predictions that any restriction on exports could cripple global tech giants, from Apple to Tesla. Yet a closer examination of the numbers and the economic logic reveals a starkly different reality. The panic, as always, seems far louder than the underlying risk.

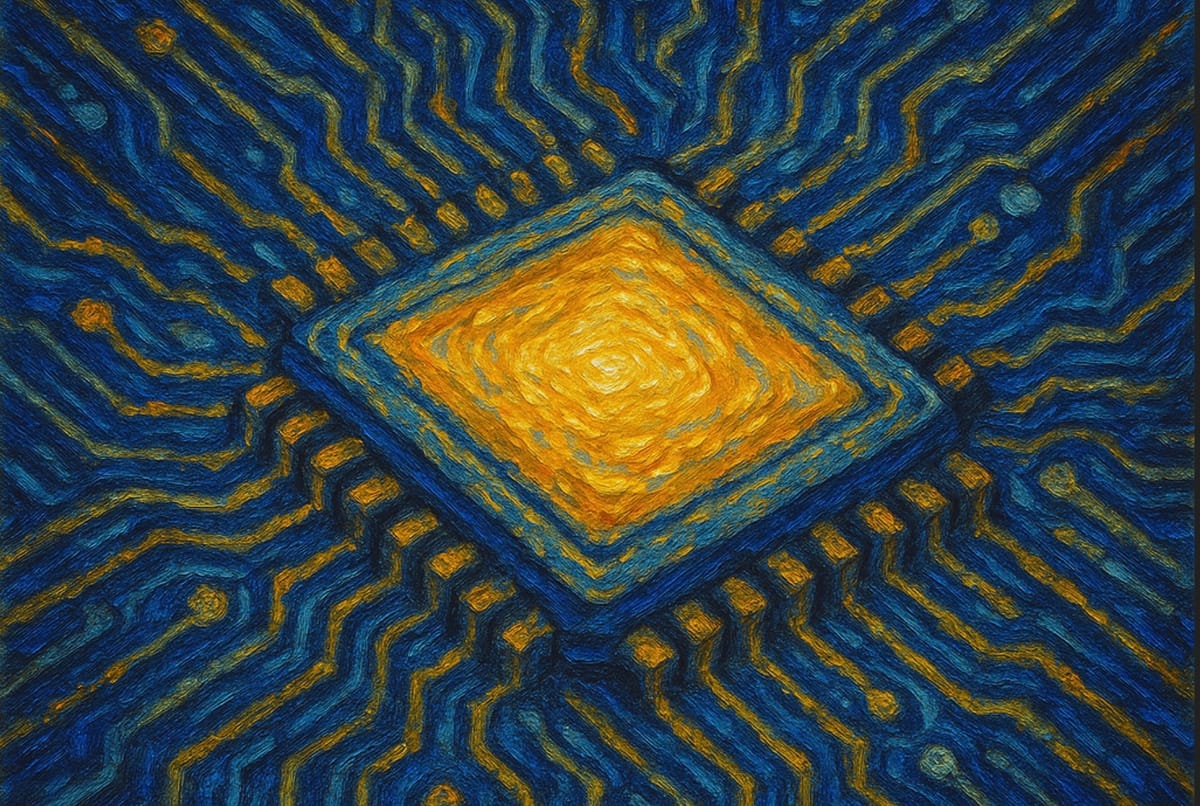

Consider the case of the iPhone, often held up as the archetype of high-tech dependence on rare minerals. Each device contains perhaps $0.30–$0.40 worth of rare earths. Let that sink in. Even if prices were to double overnight, a highly unlikely scenario, the total cost would remain trivial relative to the retail price of a flagship smartphone. For companies like Apple, which operate with immense scale and diversified supply chains, absorbing or passing on such minor increases is a routine challenge, comparable to fluctuating costs of copper, plastic, or microchips. In this context, the fear that a Chinese embargo could destroy U.S. tech is not only exaggerated, it is economically naive.

Where the burden truly falls is on Chinese suppliers of electronic devices, who generally operate on much thinner profit margins than companies like Apple. Any increase in the cost of rare earth elements would be far easier for Apple and other major tech firms to absorb than for these manufacturers, meaning China’s own electronics producers would feel the pinch first. At the same time, Chinese REE producers risk losing important U.S. clients if restrictions or embargoes are implemented, which would hit their revenues and further weaken the domestic supply chain. In practice, attempts to use REEs as a geopolitical lever could end up doing more damage to China’s own industrial base than to the intended foreign targets.

Yet beyond these immediate calculations lies a deeper lesson, the narrative of crisis has its own power, independent of facts. Media outlets, commentators, and pundits often amplify the strategic importance of REEs because it fits a compelling story of technological vulnerability and geopolitical leverage. Rare earths, in reality, are just another component in a highly adaptable, globally distributed production system. Companies like Apple and Samsung manage daily risks far more consequential than a 30-cent mineral. Supply chain disruptions, component shortages, currency fluctuations, trade tariffs, labor disputes, and even regulatory shifts exert far larger pressures on margins and operations. The rare earth story, when stripped to its economic essence, is almost trivial.

This is not to suggest that the geopolitics of rare minerals is irrelevant. Strategic considerations, national security, military applications, and industrial independence, do matter. Yet the scale of immediate disruption to consumer technology is routinely overstated. Companies have long learned to manage volatility, to diversify suppliers, and to hedge costs. The fear-inducing headlines serve more to capture attention than to inform, they substitute narrative drama for practical understanding.

Ultimately, the rare earth panic is a case study in how perception can outstrip reality. The story of China holding the world hostage via a few cents’ worth of minerals is seductive, but economically absurd. It reminds us, once again, that in modern markets, the true levers of resilience lie in adaptation, scale, and diversified risk management, not in the sensationalism of scarcity. Those who can see past the media storm, past the geopolitical posturing, and past the headlines, will recognize that the world of technology and trade is far more robust, flexible, and capable than the alarmist stories suggest.